Societies are aging exponentially thanks in part to the increase in life expectancy, and in fact the World Health Organization estimates that the proportion of older people (> 60 years) almost doubled until 2050. However, an increase in the Life expectancy is not necessarily associated with a higher quality of life. For example, a study that combined data from the National Statistics Institute and the National Health Survey showed that, despite an increase in life expectancy in Spain in the last decade, both men and women spend a majority of His old age living with chronic diseases (for example, back pain, high cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases). 1

This situation highlights the need to develop strategies aimed at improving the quality of life among older people, for which it is key to prevent chronic diseases and functional deterioration. Among many other modifiable factors, staying physically active throughout life plays a crucial role. 2 However, the reality is that we currently face a physical inactivity pandemic, especially among the elderly. It is estimated that approximately 12.5% of Europeans over 55 are physically inactive, and this figure is even higher in Spain, where one in five adults does not perform any physical activity . 3

The importance of doctors in the promotion of physical exercise

As we have commented on numerous occasions in FISSAC (we recommend you read this article about the benefits of exercising even when it is very old), the promotion of physical activity among older adults should be a priority. And for this purpose, doctors could play a key role. That is what a recent meta-analysis published in the prestigious British Medical Journal that analyzed 46 clinical trials (more than 15,000 participants) in which medical staff promoted physical activity among their patients through various interventions (either simply by advice or putting them in contact with other exercise professionals). The results showed that these interventions increased by 33% the possibilities that patients comply with international recommendations for physical activity , being more effective interventions that included a greater number of contacts with the doctor (including for example multiple visits, calls or messages). 4.5

Therefore, medical staff can be an cornerstone to favor an active life among their patients. These results would support the so -called “ sports recipe ”, a program that are already beginning to implement some communities and through which primary care doctors could prescribe their patients the practice of physical activity in a personalized way through contact with an exercise professional . Although there is still this protocol to be launched one hundred percent, in other countries there is already evidence that would support its effectiveness. For example, in a study conducted in the United Kingdom, volunteers were analyzed (the majority recruited through the primary care doctor) with 78 years on average, and it was observed that those who were prescribed to participate in an exercise program Supervised for 1 year (1-2 sessions per week in groups of around 15 participants) improved their levels of physical activity, their physical performance and their quality of life not only after the year of intervention, but also a year after . 6 In addition, although the main focus must be the health of the people, in this study another finding of great relevance was observed when implementing public health interventions: the intervention was economically profitable . 7 Specifically, it was estimated that already taking into account the cost of the training program (622 pounds per participant, including personnel and rental costs), each participant of the exercise group meant 100 pounds less of sanitary expenditure during the 2 years study regarding the participants of the control group. 7

A simple pedometer can make a difference

The derivation of the primary care doctor to participate in exercise programs supervised by a specialist seems to be, therefore, the ideal option. However, although this strategy has shown to be profitable at the cost-effective level, this is not always feasible since it requires various human and material resources (for example, exercise specialists).

To enjoy all the content, give yourself FISSAC.

Now with a 40% discount the first year . Instead of € 59.99, you pay € 35.99 (€ 3/month) . Give yourself science.

Immerse yourself in Fissac's depth and enjoy everything we have to offer you. Subscribe now and learn scientific rigor with audio-articles, webinars, masterclass and Fissac Magazine

Cancel your subscription whenever you want without obligation. Offer for an annual FISSAC subscription; only available for new subscribers. For a monthly subscription, the rate of € 6.00 each month will be automatically charged to its payment method. For an annual subscription, the introductory rate of € 35.99 and subsequently the usual rate of € 59.99 each year will be automatically charged to its payment method. Your subscription will continue until you cancel it. The cancellation enters into force at the end of its current billing period. Taxes included in the subscription price. The terms of the offer are subject to changes.

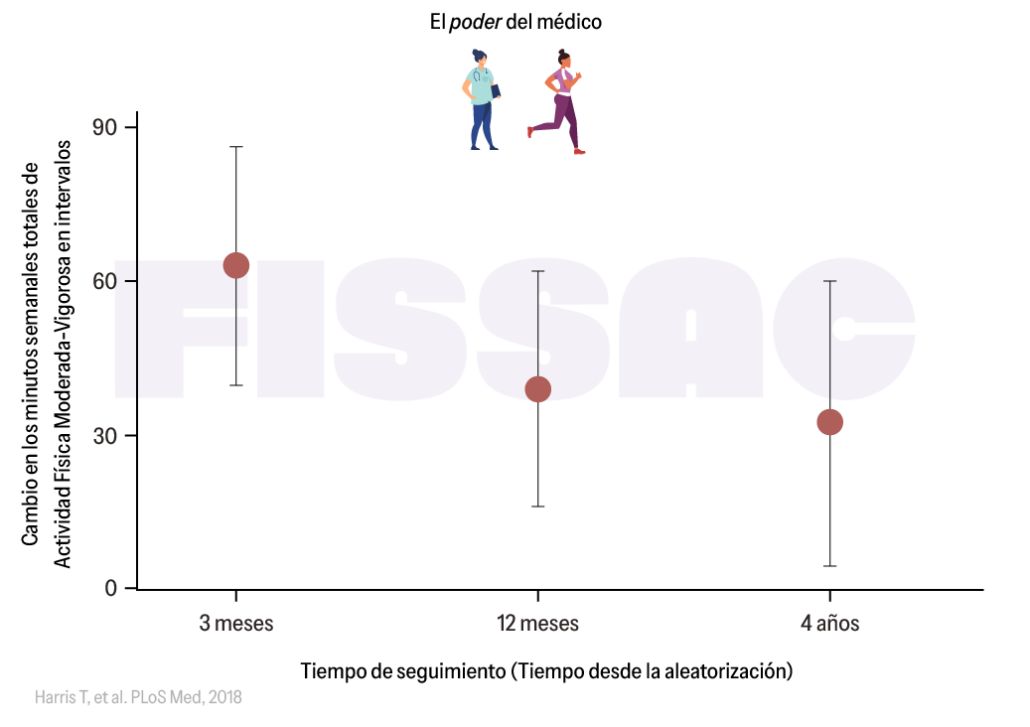

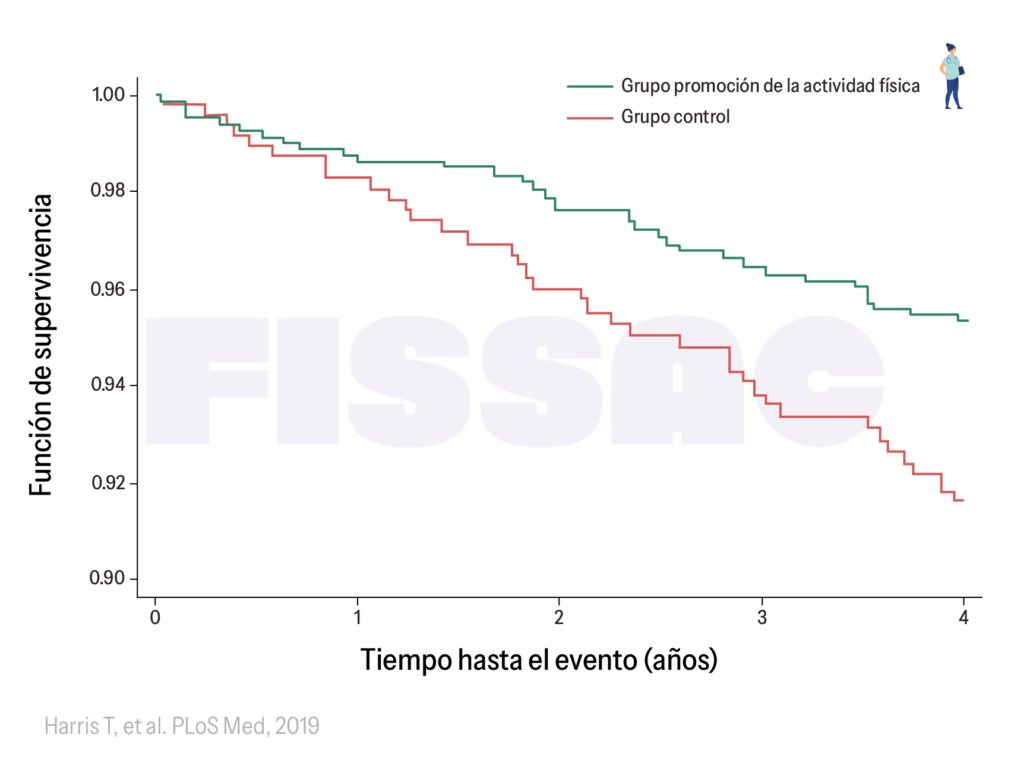

In this sense, the simple promotion of physical activity from primary care centers could be a more feasible and effective alternative. 5 In fact, different large -scale trials have found that the promotion of physical activity from primary care through recommendations in person or even by postal mail or text messages can increase the levels of physical activity, especially if provided to the Patient with a pedometer. It is what shows a clinical trial carried out in several health centers in the United Kingdom that included more than 1,000 patients, of which a group was given a podometer and were recommended to increase their levels of physical activity individually according to their Basal levels for 3 months. At the end of this period, the researchers observed that the intervention had not only been effective in the short term, increasing physical activity in 60 minutes per week after 3 months, but also in the long term, an increase of 40 minutes per week of physical activity a year after the study compared to the control group. 8 In addition, in a later follow-up, the authors observed that the benefits persisted in the long term, finding a sustained increase of 30 minutes of physical activity compared to the control group even 3-4 years after the intervention ( Figure 1 ). 9 and more importantly: the intervention managed to half reduce the risk of cardiovascular events and fractures ( Figure 2 ). 10

Figure 1. Increase in physical activity levels after a 3 -month intervention in which the doctor promoted physical activity among patients with a pedometer. Adapted from Harris et al. 9

Figure 2 . Risk of fractures 4 years after a 12 -week intervention in which the doctor promoted physical activity among patients with a pedometer. Adapted from Harris et al. 10

Physical exercise, also in hospitals

Like primary care doctors they play a key role in promoting the exercise among the elderly, as we have already mentioned on previous occasions , doctors in hospitals also have great potential in this regard. In fact, the need to promote exercise among the eldest hospitalized is even greater, since they have a particularly high risk of functional deterioration. Although older patients can be "cured" from the hospital, approximately one third of them experience the so -called disability associated with hospitalization (defined as the loss of the ability to perform one or more basic activities of daily life after hospital discharge), 11 What is associated with a higher risk of disability, institutionalization and mortality in later months. 12

Therefore, there is a strong evidence that hospital exercise interventions are effective in preventing functional deterioration after acute hospitalization not only to hospital discharge, but also months later. 13 In fact, different essays in Spanish hospitals have shown that even relatively simple exercise interventions made in the hospital (including for example sitting and getting out of bed, or walking through the hall) are effective in preventing functional deterioration. 14–16

However, we all know that unfortunately these interventions are not yet routinely included in hospitals, perhaps partly due to lack of human and material resources (for example, lack of exercise specialists). In this sense, it is important to emphasize that, even if supervised exercise programs are not feasible, different studies in different countries have shown that something as simple as giving patients a patometer (with the aim of encouraging physical activity by counting The number of steps) can increase your physical activity levels, with the consequent benefits in physical function. 17 For example, a study in 255 greater in Australia showed that providing feedback on their daily levels of physical activity and establishing goals was enough to increase their physical activity levels. 18

Conclusions and implications

Health personnel have enormous impact throughout the population, and especially among the elderly. In this sense, more and more evidence supports the important role that doctors and nurses can have in the promotion of physical activity in this population, particularly from primary care centers, but also from geriatrics units. Whenever possible, the derivation to exercise programs supervised by an exercise specialist is convenient, but we should not ignore that even simpler actions such as the simple promotion of physical activity (that is, recommend increasing physical activity levels) have proven to be effective, especially if accompanied by the use of a pomometer or other feedback tool (for example, a mobile application).

It should be noted that, despite these findings, among other limitations (including lack of time) doctors continue to perceive that one of their barriers when recommending exercise programs or physical activity is that they have little knowledge on the subject. 19 For this reason, if we want the so -called sports recipe to be a success, it is necessary not only to provide greater human and material resources to public health, but also to implement interventions to educate and encourage doctors to promote physical activity, as well as Facilitate derivation routes between doctors and specialists in physical exercise. 20

References:

1. Zueras P, Rentería E. Trends in Disease-Free Life Expercy Age Age 65 In Spain: Diverging Patterns By Sex, Region and Disease. Plos One . 2020; 15 (11 November): 1-15. DOI: 10.1371/Journal.pone.0240923

2. Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. BR J SPORTS MED . 2020; 54 (24): 1451-1462. DOI: 10.1136/BJSports-2020-102955

3. Gomes M, Figueiredo D, Teixeira L, et al. Physical inactivity Among Older Adults Across Europe Based on The Share Database. Ageing Ageing . 2017; 46 (1): 71-77. DOI: 10.1093/Ageing/AFW165

4. Orrow G, Kinmonth al, Sanderson S, Sutton S. Effectiveness of Physical Activity Promotion Based in Primary Care: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. BMJ . 2012; 344 (7850): 16. DOI: 10.1136/BMJ.E1389

5. Kettle VE, Madigan CD, Coombe A, et al. Effectiveness of Physical Activity Interventions delivered Or prompted by Health Professionals in Primary Care Settings: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. BMJ . 2022; 376: 1-13. DOI: 10.1136/BMJ-2021-068465

6. Stathi A, Greaves CJ, Thompson JL, et al. Effect of A Physical Activity and Behaviour Maintenance Program on Functional Mobility Decline in Older Adults: The React (Retirement in Action) Randomized Controlled Trial. Lancet Public Heal . 2022; 7 (4): E316-E326. DOI: 10.1016/S2468-2667 (22) 00004-4

7. Snowsill TM, Stathi A, Green C, et al. COSE-Effectiveness of a Physical Activity and Behaviour Maintenance Program on Functional Mobility Decline in Older Adults: An Economic Evaluation of the React (Retirement in Action) Trial. Lancet Public Heal . 2022; 7 (4): E327-E334. DOI: 10.1016/S2468-2667 (22) 00030-5

8. Harris T, Kerry SM, Victor Cr, et al. A Primary Care Nurse-Delivered Walking Intervention in Older Adults: PACE (Pedometter Accelerometer Consultation Evaluation) -Lift Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. PLOS MED . 2015; 12 (2): 1-23. DOI: 10.1371/Journal.pmed.1001783

9. Harris T, Kerry SM, Limb es, et al. Physical Activity Levels in Adults and Older Adults 3–4 Years AFTER PEDOMETER-BASED WALKING INTERVENCIONS: Long-Term Follow-up of participants from Two Randomized Controlled Trials in UK Primary Care. PLOS MED . 2018; 15 (3): 1-16. DOI: 10.1371/Journal.pmed.1002526

10. Harris T, Limb Es, Hushing F, et al. Effect of Pedometer-Based Walking Interventions on Long-Term Health Outcomes: Prospective 4-YEAR FOLLOW-UP OF TWO RANDOMISED CONTROLLED TRIALS USING ROUTINE PRIMARY CARE DATA. PLOS MED . 2019; 16 (6): 1-20. DOI: 10.1371/Journal.pmed.1002836

11. Loyd C, Markland Ad, Zhang and, et al. Prevalence of Hospital-Associated Disability in Older Adults: A Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc . 2020; 21 (4): 455-461. DOI: 10.1016/J.JAMDA.2019.09.015

12. Boyd C, Landefeld C, Counsell S, et al. Recovery in Activities of Daily Living Among Older Adults Following Hospitalization for Acotte Medical Illness. J AM GERIAT SOC . 2008; 56 (12): 2171-2179. DOI: 10.1111/J.1532-5415.2008.02023.X.Recovery

13. Valenzuela P, Morales J, Castillo-García A, et al. Effects of Exercise Interventions on the Functional Status of Acotely Hospitalised Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ageing res rev . 2020; 61: 101076.

14. Martínez-Velilla N, Casas-Herrero N, Zambon-Ferraresi F, et al. Effect of Exercise Intervention on Functional Decline in Vry Elderly Patients During Acute Hospitalization: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA INTER MED . 2019; 179 (1): 28-36.

15. Ortiz-Alonso J, Bustamante -ra N, Valenzuela PL, et al. Effect of to simple exercise program on hospitalization-asociated disability in Older Patients: A Randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc . 2020; 21 (4). DOI: 10.1016/J.JAMDA.2019.11.027

16. Rodriguez-Lopez C, Butler-Cava J, Zarralanga-Lasobras T, et al. Exercise Intervention and Hospital-Associated Disability A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. Jama Netw Open . 2024; 7 (2): E2355103. DOI: 10.1001/JAMANETWORKEPEN.2023.55103

17. Szeto K, Arnold J, Singh B, Gower B, Simpson Cem, Maher C. Interventions Using Wearable Activity Trackers to Improve Patient Physical Activity and Other Outcomes in Adults Who Are Hospitalized: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Jama Netw Open . 2023; 6 (6). DOI: 10.1001/JAMANETWORKEPEN.2023.18478

18. Peel NM, Paul Sk, Cameron Id, Crotty M, Kurle Se, Gray Lc. Promoting Activity in Geriatric Rehabilitation: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Accelerometry. Plos One . 2016; 11 (8): 1-13. DOI: 10.1371/Journal.pone.0160906

19. Albert FA, Crowe MJ, Malau-Aduli Aeo, Malau-Aduli Bs. Physical Activity Promotion: A Systematic Review of the Perceptions of Healthcare Professionals. Int j Envodon Res Public Health . 2020; 17 (12): 1-36. DOI: 10.3390/IJERPH17124358

20. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Action on Physical Activity 2018-2030: More Active People for a Healthier World . World Health Organization; 2018. DOI: 10.1016/J.Jpolmod. 2006.06.007