The human body is a practically perfect biological machine that uses its energy in maintaining the balance of all the systems that compose it, many times despite the environment in which it lives or the intentional stimuli to which we submit it. For lovers of exploration of the own limits, the ability to adapt our organism is a gift from the gods. We know that, before a physiological challenge, the organism uses its arts not only to overcome it, but to go a little further. As if somehow would like to protect themselves to similar future stimuli that could alter their stability. This allows us to play with the imbalances to which we expose it (exercise, nutrition, altitude, cold, heat ...) to achieve different adaptations and, thus, in a controlled stressful dance, push our skills towards new horizons.

In this sense, it is fascinating to know how the organism reacts to the extreme altitude, a tremendously hostile place for life not only because of the intrinsic difficulties that the mountains are entrusted, the extreme cold or the isolation, but because of the physiological challenge that the Lack of oxygen (hypoxia) on our cellular system. Surely all of us who have ever started in the world of hypoxia have asked ourselves the same question: how can it be that a person with so little oxygen in the blood, that any doctor would urgently take the UCI, not capable not only to survive at altitude but to climb and make decisions? To answer this question we must first understand what we mean in this text when we talk about hypoxia.

A game of pressures to breathe on the roof of the world

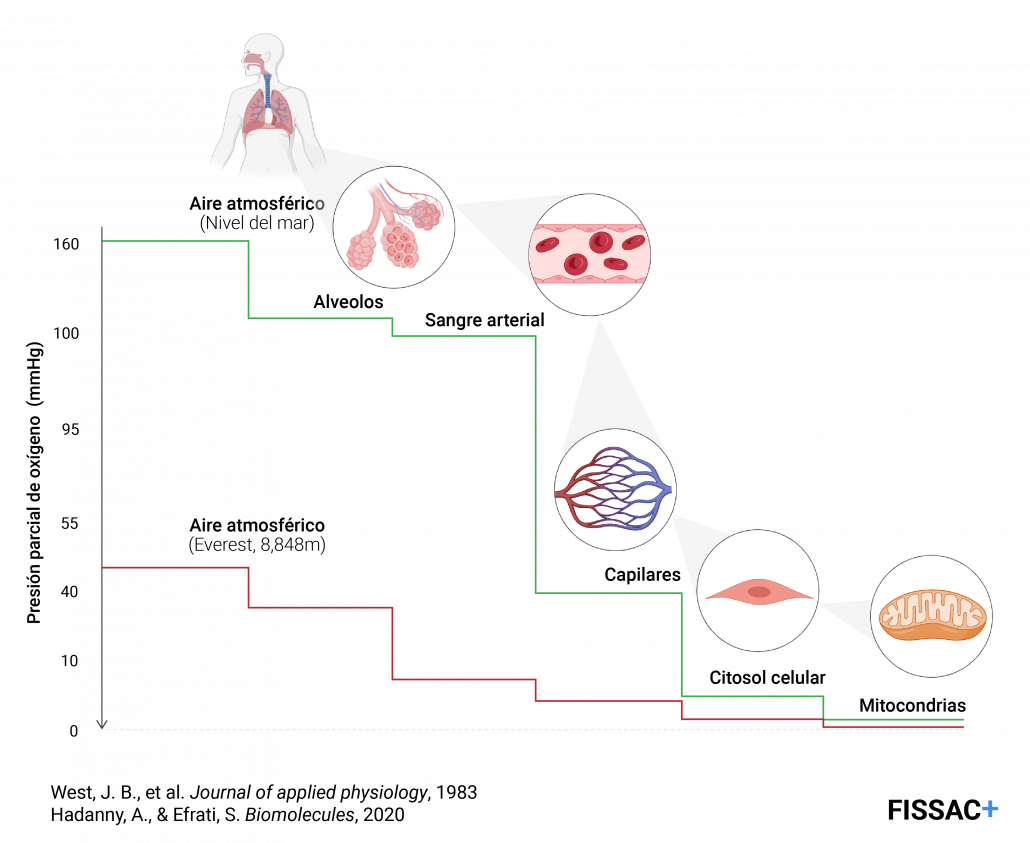

The amount of oxygen contained in the air that is breathed at the EVEST Above our heads. Somehow, at the same time that we ascend a mountain, we "climb" meters of atmosphere and the pressure that it exerts on us is getting smaller. This is superlative, since oxygen travels through our body thanks to the difference in pressures (more pressure at less pressure). If we make a parallel with a waterfall, the more inclination it has, the more easily the water falls. Something similar happens with oxygen: if there is more pressure in the lungs than in the blood, it spreads with few difficulties. If the pressure difference is lower, its transport is less effective. And so at all levels until reaching the mitochondria, which are responsible for transforming oxygen into energy so that we can work. This is the basis of the term Hypobaric hypoxia: there is oxygen, but it is not available (Figure 1). Therefore, at the Everest Summit (where atmospheric pressure is a third with respect to the sea level) and using all our available energy, with those levels of cellular oxygen, most mortals could do nothing more than be Quiet and breathe, at best. In other words, the physical capacity of any individual at the highest summit on the planet is reduced to approximately 80% compared to the one at sea level.

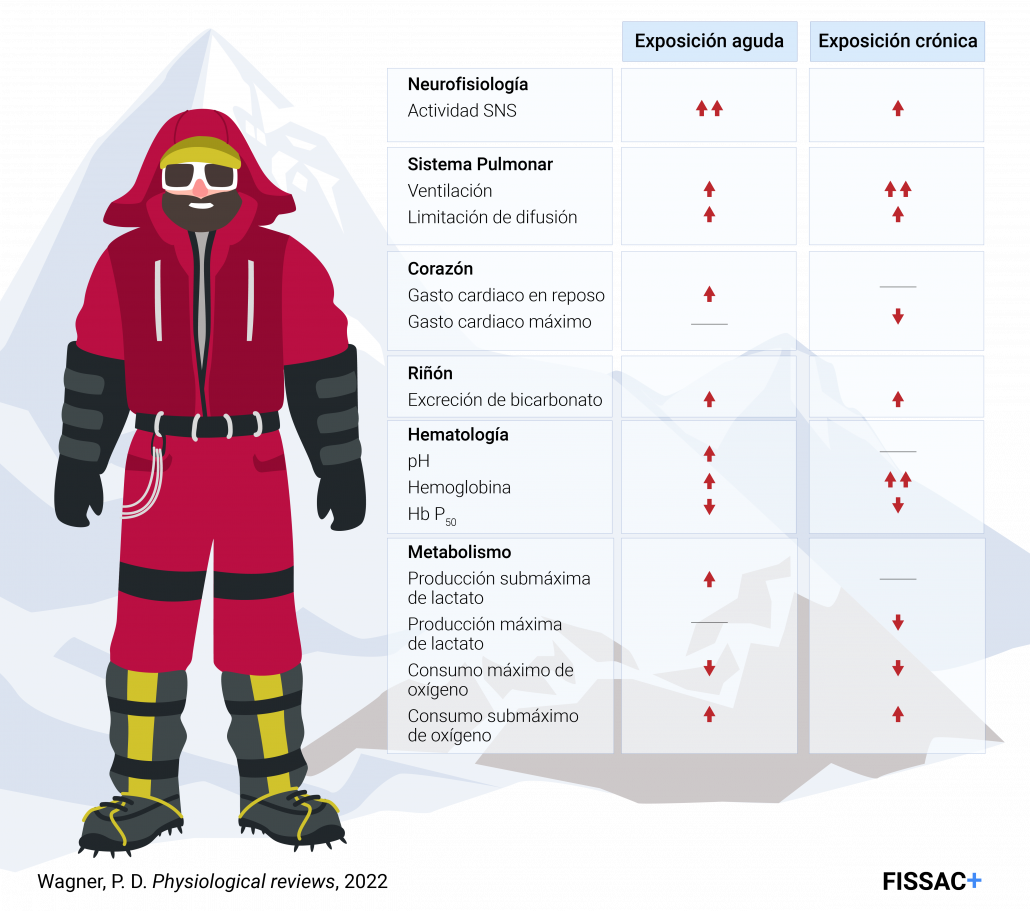

If we now enter the relationship between the human being and the hypoxia, we see that up to 2500 or 3000 meters of altitude the body has the ability to compensate for changes in atmospheric pressure without major problems, so that the amount of oxygen In blood it is barely modified. From this point, homeostatic capacity is compromised and the body displays its particular dance of responses: the first changes happen quickly and allow immediate survival but paying a high energy expenditure that we cannot maintain for a long time. As in most alarm situations, the answer is very effective, but not very efficient. Now, if the exposure lasts enough, the agency begins to orchestrate a series of measures that, although they are slower to be carried out, allow more economical energy more economically and consequently more lasting over time.

In this sense, the discovery of the HIF (of English, inducible factor ), a factor that under normal conditions is not transcribed but that in the absence of oxygen triggers a series of changes in many systems, shed light on the origin of the mechanisms of long -term acclimatization. These are based on adjusting the anatomy and metabolic functions to the low oxygen availability with a double objective: intensify the mechanisms responsible for the transport of oxygen to the cells and minimize the organism's oxygen spending. A brilliant strategy that justifies the ability to acclimatize to moderate altitude and the exceptional possibility that some people can not only survive, but to exercise in the extreme altitude. So much so that, despite the fact that an abrupt rise to 5000 meters would probably trigger altitude diseases and even death in exposed people, with sufficient time and acclimatization. Alpeistas can remain for months above this level.

Why are we so effective in battle against the lack of oxygen?

Considering that nature does not usually use much energy in processes not necessary for survival, it is the less curious to see the immense ability to adapt the human being to altitude and not to other environmental stressors such as temperature. What interest can our biology have in which we survive so effectively to lack of oxygen? The answer is not found in the mountains, but in the evolutionary fight. The body has learned the response systems against the lack of oxygen at a atavic way, since a multitude of physiological and pathological processes entail hypoxia to a lesser or greater degree. We can illustrate this with several examples: during the formation of the embryo in the maternal belly, there is a hypoxic component that must be tolerated; Intense physical exercise causes lack of oxygen in some tissues with which we often deal with; Or, from a pathophysiological point of view, few diseases escape the lack of oxygen as a cause or consequence: cancer, myocardial infarctions, cerebral ischemia and many metabolic diseases have as its common denominator the fight against the scarcity of oxygen.

This is why hypoxia is not an unknown language for the alpinist's body. With a good genetic predisposition, taking care of the promotion strategy, respecting the breaks and with the necessary time and energy, gradually higher altitudes can be tolerated. It is evident that according to more altitude it is achieved, the more difficulties the body has to compensate for the lack of oxygen. In fact, there is an altitude from which acclimatization is impossible and survival is intimately linked to the time we remain there. From that point, variable between individuals, the body must make such an effort to survive that energy expenditure is unimaginable, so that any type of extra effort, such as walking, leads to the alpenist at the edge of their physical abilities and mental Reinhold Messner, the first human being that reached the EVrest Summit without supplementary oxygen thus described his experience: “As we climb, we have to lie down to recover our breath ... breathing becomes so exhausted that we barely have strength to move forward. I am nothing more than a lonely, small and panting lung floating on fogs and summits. "

Since he and Habeler would hop the highest summit on the planet by their own means and against scientific opinion (which considered the deed as something physiologically impossible for any human being), the interest in altitude exploration has remained intact between the few people who have the gift of high climbingism. Over the years and discreetly, they have been dripping great ascents to the highest summits of the planet that have touched the limit of human tolerance and that have probably not received the sports recognition they deserved, overshadowed by mass tourism In height.

The "alpine style", the minimalist solution to the great peaks

This modality of alpineism in self -sufficiency, which prevails the search of alpine challenge without external aids that the strings are fixed, indicate the way or open the trace in the snow, which rejects the use of drugs and bottled oxygen to climb, which values The first ascents by the merit associated with the exploration, is called the "alpine style ". It is putting the "how" above the "what ascends", without pretending to minimize the physiological challenge ; Do not conquer a summit at any price, but to put the value on the path that is chosen to reach it, accepting and hugging their own limits against a tremendously hostile atmosphere. It is evident that the chances of success, if we consider success such as reaching the summit, are much lower.

To enjoy all the content, give yourself FISSAC.

Now with a 40% discount the first year . Instead of € 59.99, you pay € 35.99 (€ 3/month) . Give yourself science.

Immerse yourself in Fissac's depth and enjoy everything we have to offer you. Subscribe now and learn scientific rigor with audio-articles, webinars, masterclass and Fissac Magazine

Cancel your subscription whenever you want without obligation. Offer for an annual FISSAC subscription; only available for new subscribers. For a monthly subscription, the rate of € 6.00 each month will be automatically charged to its payment method. For an annual subscription, the introductory rate of € 35.99 and subsequently the usual rate of € 59.99 each year will be automatically charged to its payment method. Your subscription will continue until you cancel it. The cancellation enters into force at the end of its current billing period. Taxes included in the subscription price. The terms of the offer are subject to changes.

Precisely because of the risk involved of these ascents and against the image of the maiden of the average in several disciplines (ice climb, glacier progression, mixed climbing, ...), which allows them not only to survive the extreme altitude, but take decisions, climb and advance at a considerable speed. Considering this last point, one of the biggest challenges of climbing art is the balance between the necessary time in height to get the body to acclimate and the implicit degradation that entails the fact of the altitude stay itself, so that the capacity To move quickly through the mountain, it can be considered as a physiological safety element. Day after day, the deleterious effects of altitude are making a mella in the mountaineer and translate into lack of sleep, malnutrition, dehydration, muscle atrophy, deserting and digestive problems, not forgetting that the hypoxic environment clouds the judgment, motivation and decision making. It is an inevitable degeneration that the body pays for being in an environment in which it can scarce.

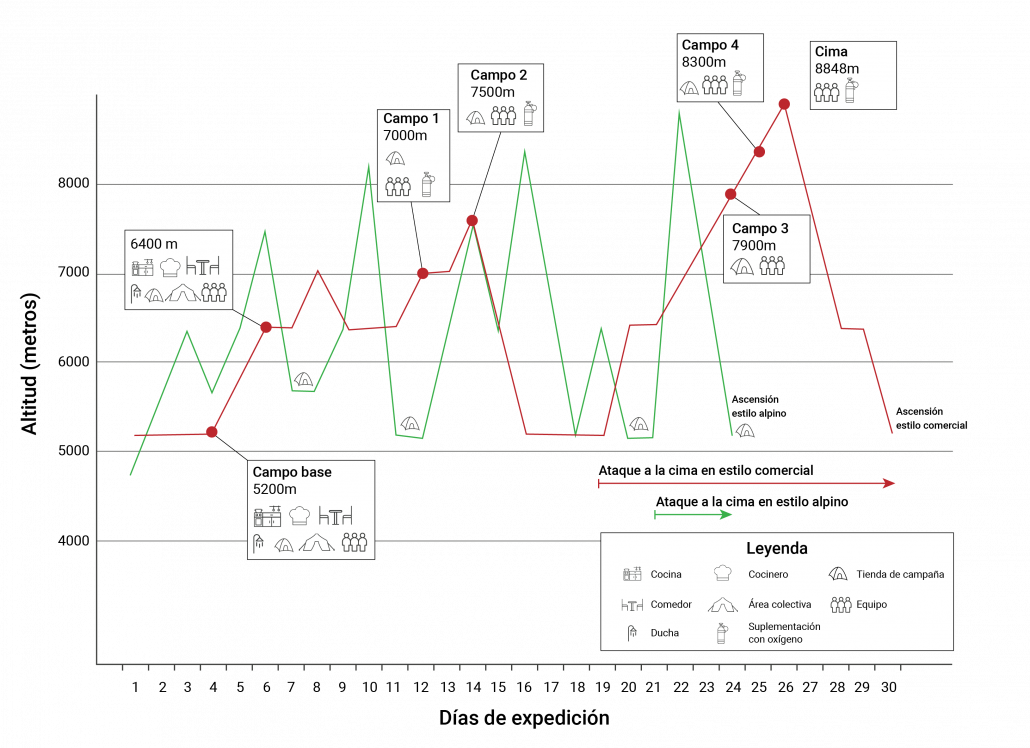

In this sense, the acclimatization profiles of current mountaineering, although they do not follow a constant pattern, tend to prioritize to be able to feed, hydrate and sleep well to moderate dimensions, giving sufficient hypoxic stimuli so that the body knows that the acclimatization mechanisms should start . This implies the ability to overcome great slopes. Gone are the heavy expeditions that slowly advanced through the mountain investing long days and endless nights at extreme altitude. How long at height each body needs to acclimatize enough is difficult to value, but this knowledge is closely linked to the experience. The mountaineer knows his body, listens to the alarm signs that he emits and acts accordingly.

It is understandable that the strategy of this type of expeditions must be cared for until the last detail since, in this context, absolutely everything is a superlative challenge: to carry the weight of the technical and protection material without the help of porters, transport the necessary fuel To cook and hydrate, merge snow for hours at a desperately slow pace after a strenuous day, protect yourself from cold or manage uncertainty on non -explored roads previously; And all this subject to a multitude of variables such as the conditions of the road, the thickness of the snow, the meteorology, the state of acclimatization, accumulated fatigue or food, fuel and available water. A good part of the planning is invested, precisely, in voluntarily saving oxygen consumption in the most unlikely forms: everything is measured in terms of weight and utility, from food or the essential technical material to the pills inside the kit. As some authors have defined, the alpine style is something like the art of efficiency, the "minimum option" against the mountain challenge.

References:

1. West JB, Hacket Ph, Maret Kh, Milledge JS, Peters RM, Pizzo CJ, et al. PULMONARY GAS EXCHANGE ON THE SUMMIT OF MOUNTEEST. J Appl Physiol [Internet]. 1983 SEP 1; 55 (3): 678–87. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1983.55.3.678

2. Wagner pd. Altitude Physiology Then (1921) and Now (2021): Meat on the Bones. Physiol Rev [Internet]. 2021 SEP 27; 102 (1): 323–32. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00033.2021