Dementia is one of the greatest causes of disability and loss of independence among the elderly. In fact, it is estimated that approximately 46 million people have dementia worldwide, and due among other things to the aging of the population, it is estimated that this figure will double every 20 years (1).

There are many variables that can condition the risk of dementia, including from genetic factors to others related to lifestyle. Within the latter, physical exercise seems to play a fundamental role, as confirmed by numerous studies. For example, physical exercise has shown increase executive function and memory in healthy elderly and even those who already have cognitive impairment (2). In fact, as we previously commented in an article , physical exercise has shown that it can even prevent diseases such as Alzheimer > 150 minutes/week of moderate physical activity or 75 minutes/week of intense physical activity) reduces the risk of suffering this disease (3).

The exact mechanisms through which the exercise could play a protective role against dementia are not clear, but the evidence is increasingly clear about some of them (you can read a complete review that we write on the subject here (4) and in this article in Fissac). One of the most widely demonstrated mechanisms is the prevention of risk factors such as overweight, hypertension or diabetes, which are associated with a greater risk of neurodegeneration. On the other hand, long -term exercise improves redox and inflammatory balance (that is, reduces oxidative stress and inflammation), also contributing to prevent neurodegeneration. In addition, it has been observed that the so -called “exerquinas” (myocines and other molecules, such as the precursor of the irisin, FNDC5, which are released to the bloodstream mainly by the muscles during exercise) could transfer the hematoencephalic barrier and produce effects neurotrophic. Similarly, it has been observed that changes at the metabolic level that can occur with exercise as an increase the concentration of lactate or ketone bodies can also favor positive responses at the brain level.

To enjoy all the content, use FISSAC+

Immerse yourself in Fissac's depth and enjoy everything we have to offer you. Subscribe now and learn scientific rigor with audio-articles, webinars, masterclass and Fissac Magazine

Instead of € 59.99 you pay € 29.99 the first year. Give yourself science.

What do subscribers think?

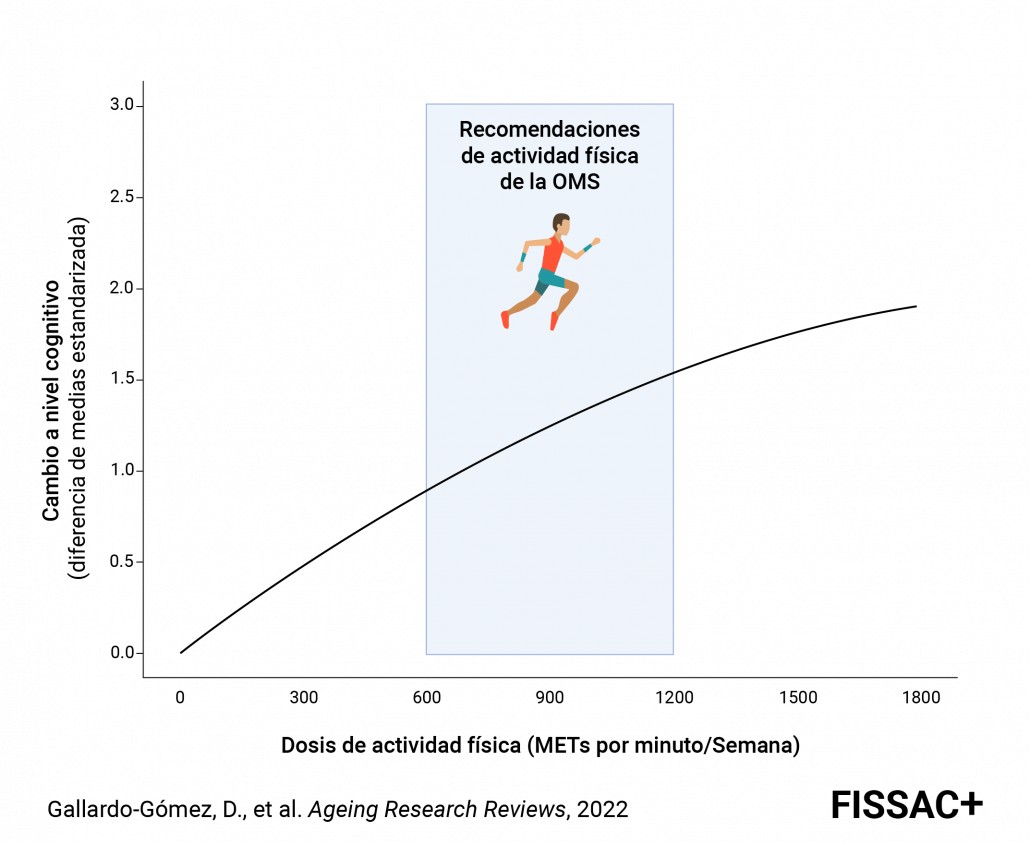

Despite all these mechanisms and the epidemiological evidence that supports the benefits of exercise in cognitive performance, to date it was unknown if all types and doses of exercise produce the same benefits. In this sense, a meta-analysis has been published that has included a total of 44 studies conducted in almost 5,000 older people and who have analyzed the effects of an exercise intervention with respect to a control group that did not exercise (5). The authors observed that the relationship between the exercise dose and the benefits at the cognitive level was not linear. That is, the benefits increased to a certain amount of exercise, but from that dose the benefits increased only slightly. Specifically, the benefits were doubled if 1200 MET/min were performed (equivalent to the upper limit of WHO recommendations, that is, 300 weekly minutes of moderate activity or 150 minutes per week of vigorous activity) compared to whether 600 were made Met/min (equivalent to the lower limit of WHO recommendations, 150 weekly minutes of moderate activity or 75 vigorous activity). However, although performing more exercise provided more benefits at the cognitive level, the slope of this relationship decreased slightly ( Figure 1 ).

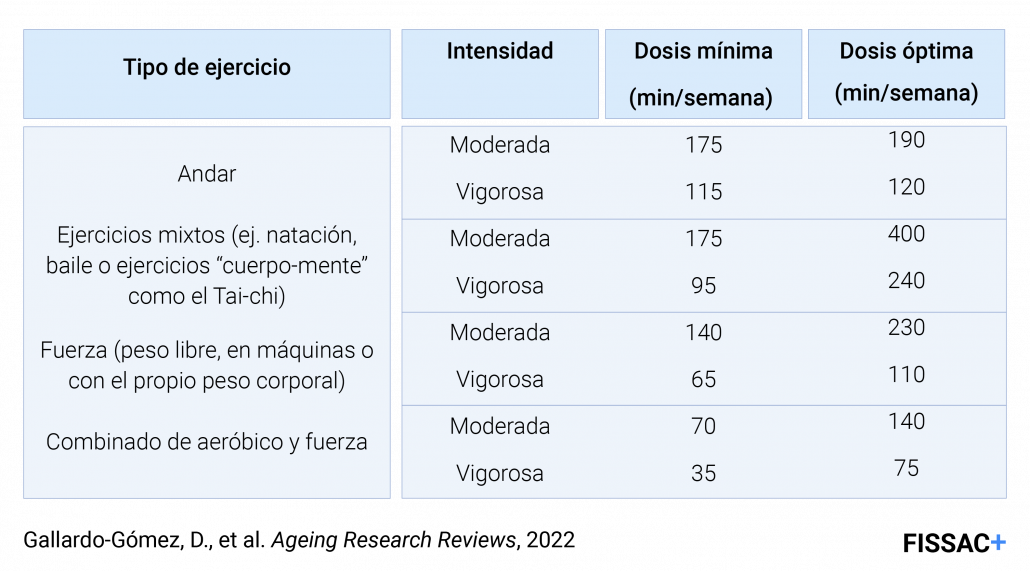

On the other hand, the authors also analyzed the relationship between the exercise dose and the benefits at the cognitive level attending to different types of exercise, and found that this relationship varies from one exercise to another. Thus, for example, the greatest effects for aerobic exercise were 1800 MET/min per week (we attached proposal with examples in Table 1), while for the exercise of force with the body weight itself, with free weight or with Machines, the greatest benefits were achieved with half the dose (900 Met/Min per week). With these data, the authors propose some recommendations of the exercises that would produce the greatest benefits at the cognitive level, as well as the minimum exercise to be carried out ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Minimum and optimal exercise recommendations according to the benefits observed in cognitive performance in the elderly. Table adapted from Gallardo-Gómez et al. (5).

Conclusions

Exercise is shown as a fundamental strategy to prevent cognitive deterioration in the elderly. This recently published meta-analysis allows us to also extract some valuable conclusions, among which we can emphasize that performing any exercise is better than doing nothing, and that in general the more exercise we carry out the greater the benefits, although the relationship is not totally linear When the upper limit of WHO recommendations is exceeded. In addition, we observe that the benefits can depend on the exercise carried out, and while the necessary dose to obtain the greatest benefits can be very high if we only go to moderate intensity (requiring for example 190 minutes per week), this dose decreases significantly if we perform other exercises such as the combination of aerobic exercise and force to vigorous intensity (just requiring only 75 per week).

References:

1. Prince M. The Global Impact of Dementia: An Analysis of Prevalence, Insence, Cost and Trends. Vol. 1, World Alzheimer Report 2015. 2015.

2. Sanders LMJ, Hortobágyi T, Gemert S la B van, van der Zee Ea, Van Heuvelen MJG. DOSE-RespiShip Between Exercise and Cognitive Function in Older Adults With and Without Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Plos One. 2019; 14 (1): 1–24.

3. SANTOS-LOZANO A, Pareja-Galeano H, Sanchis-Gomar F, Quindós-Rubial M, Fiuza-Luces C, Cristi-Montero C, et al. Physical Activity and Alzheimer Disease: A Protective Association. MAY CLIN PROC. 2016; 91 (8): 999–1020.

4. Valenzuela PL, Castillo-García A, Morales JS, from Villa P, Hampel H, Emanuele E, et al. EXERCISE BENEFITS ON ALZHEIMER'S DIEW: STATE-OF-THE-SCIENCE. Ageing Res Rev. 2020; 62 (May): 101108.

5th Gallardo-Gomez D, from the Pozo-Cruz J, Noetel M, Álvarez-Barbosa F, Alfonso-Rosa R, B DP-C. OPTIMAL DOSE AND TYPE OF EXERCISE TO IMPROVE COGNITIVE FUNCTION IN OLDER ADULTS: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND BAYESIAN MODEL-BASED NETWORK META-ANALYSIS OF RCTS. Ageing Res Rev. 2022; in press.